-

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

-

Japan's Sanae Takaichi: Iron Lady 2.0 hopes for election boost

-

Italy set for 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony

Italy set for 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony

-

Hong Kong to sentence media mogul Jimmy Lai on Monday

-

Pressure on Townsend as Scots face Italy in Six Nations

Pressure on Townsend as Scots face Italy in Six Nations

-

Taiwan's political standoff stalls $40 bn defence plan

-

Inter eyeing chance to put pressure on title rivals Milan

Inter eyeing chance to put pressure on title rivals Milan

-

Arbeloa's Real Madrid seeking consistency over magic

-

Dortmund dare to dream as Bayern's title march falters

Dortmund dare to dream as Bayern's title march falters

-

PSG brace for tough run as 'strange' Marseille come to town

-

Japan PM wins Trump backing ahead of snap election

Japan PM wins Trump backing ahead of snap election

-

AI tools fabricate Epstein images 'in seconds,' study says

-

Asian markets extend global retreat as tech worries build

Asian markets extend global retreat as tech worries build

-

Sells like teen spirit? Cobain's 'Nevermind' guitar up for sale

-

Thailand votes after three prime ministers in two years

Thailand votes after three prime ministers in two years

-

UK royal finances in spotlight after Andrew's downfall

-

Diplomatic shift and elections see Armenia battle Russian disinformation

Diplomatic shift and elections see Armenia battle Russian disinformation

-

Undercover probe finds Australian pubs short-pouring beer

-

Epstein fallout triggers resignations, probes

Epstein fallout triggers resignations, probes

-

The banking fraud scandal rattling Brazil's elite

-

Party or politics? All eyes on Bad Bunny at Super Bowl

Party or politics? All eyes on Bad Bunny at Super Bowl

-

Man City confront Anfield hoodoo as Arsenal eye Premier League crown

-

Patriots seek Super Bowl history in Seahawks showdown

Patriots seek Super Bowl history in Seahawks showdown

-

Gotterup leads Phoenix Open as Scheffler struggles

-

In show of support, Canada, France open consulates in Greenland

In show of support, Canada, France open consulates in Greenland

-

'Save the Post': Hundreds protest cuts at famed US newspaper

-

New Zealand deputy PM defends claims colonisation good for Maori

New Zealand deputy PM defends claims colonisation good for Maori

-

Amazon shares plunge as AI costs climb

-

Galthie lauds France's remarkable attacking display against Ireland

Galthie lauds France's remarkable attacking display against Ireland

-

Argentina govt launches account to debunk 'lies' about Milei

-

Australia drug kingpin walks free after police informant scandal

Australia drug kingpin walks free after police informant scandal

-

Dupont wants more after France sparkle and then wobble against Ireland

-

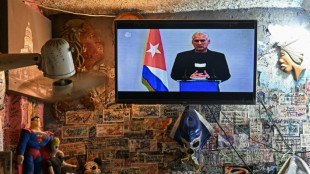

Cuba says willing to talk to US, 'without pressure'

Cuba says willing to talk to US, 'without pressure'

-

NFL names 49ers to face Rams in Aussie regular-season debut

-

Bielle-Biarrey sparkles as rampant France beat Ireland in Six Nations

Bielle-Biarrey sparkles as rampant France beat Ireland in Six Nations

-

Flame arrives in Milan for Winter Olympics ceremony

-

Olympic big air champion Su survives scare

Olympic big air champion Su survives scare

-

89 kidnapped Nigerian Christians released

-

Cuba willing to talk to US, 'without pressure'

Cuba willing to talk to US, 'without pressure'

-

Famine spreading in Sudan's Darfur, UN-backed experts warn

-

2026 Winter Olympics flame arrives in Milan

2026 Winter Olympics flame arrives in Milan

-

Congo-Brazzaville's veteran president declares re-election run

-

Olympic snowboard star Chloe Kim proud to represent 'diverse' USA

Olympic snowboard star Chloe Kim proud to represent 'diverse' USA

-

Iran filmmaker Panahi fears Iranians' interests will be 'sacrificed' in US talks

-

Leicester at risk of relegation after six-point deduction

Leicester at risk of relegation after six-point deduction

-

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, raises calls to postpone Portugal vote

-

Trump urges new nuclear treaty after Russia agreement ends

Trump urges new nuclear treaty after Russia agreement ends

-

'Burned in their houses': Nigerians recount horror of massacre

-

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate, affirms auto sector's future is electric

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate, affirms auto sector's future is electric

-

Emotional reunions, dashed hopes as Ukraine soldiers released

Ostrich and emu ancestor could fly, scientists discover

How did the ostrich cross the ocean?

It may sound like a joke, but scientists have long been puzzled by how the family of birds that includes African ostriches, Australian emus and cassowaries, New Zealand kiwis and South American rheas spread across the world -- given that none of them can fly.

However, a study published Wednesday may have found the answer to this mystery: the family's oldest-known ancestors were able to take wing.

The only currently living member of this bird family -- which is called palaeognaths -- capable of flight is the tinamous in Central and South America. But even then, the shy birds can only fly over short distances when they need to escape danger or clear obstacles.

Given this ineptitude in the air, scientists have struggled to explain how palaeognaths became so far-flung.

Some assumed that the birds' ancestors were split up when the supercontinent Gondwana started breaking up 160 million years ago, creating South America, Africa, Australia, India, New Zealand and Antarctica.

However, genetic research has shown that "the evolutionary splits between palaeognath species happened long after the continents had already separated," lead study author Klara Widrig of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History told AFP.

- Wing and a prayer -

Widrig and colleagues analysed the specimen of a lithornithid, the oldest palaeognath group for which fossils have been discovered. They lived during the Paleogene period 66-23 million years ago.

The fossil of the bird Lithornis promiscuus was first found in the US state of Wyoming, but had been sitting in the Smithsonian museum's collection.

"Because bird bones tend to be delicate, they are often crushed during the process of fossilisation, but this one was not," she said.

"Crucially for this study, it retained its original shape," Widrig added. This allowed the researchers to scan the animal's breastbone, which is where the muscles that enable flight would have been attached.

They determined that Lithornis promiscuus was able to fly -- either by continuously beating its wings or alternating between flapping and gliding.

But this discovery prompts another question: why did these birds give up the power of flight?

- Taking to the ground -

"Birds tend to evolve flightlessness when two important conditions are met: they have to be able to obtain all their food on the ground, and there cannot be any predators to threaten them," Widrig explained.

Other research has also recently revealed that lithornithids may have had a bony organ on the tip of their beaks which made them excel at foraging for insects.

But what about the second condition -- a lack of predators?

Widrig suspects that palaeognath ancestors likely started evolving towards flightlessness after dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago.

"With all the major predators gone, ground-feeding birds would have been free to become flightless, which would have saved them a lot of energy," she said.

The small mammals that survived the event that wiped out the dinosaurs -- thought to have been a huge asteroid -- would have taken some time to evolve into predators.

This would have given flightless birds "time to adapt by becoming swift runners" like the emu, ostrich and rhea -- or even "becoming themselves dangerous and intimidating, like the cassowary," she said.

The study was published in the Royal Society's Biology Letters journal.

H.Thompson--AT